Note: this interview originally appeared in my regular newsletter. You can sign up for it here.

Note 2: This Q&A originally ran in my July 2024 newsletter.

Note 3: The newsletter is brought to you by the made-in-italy, designer cap brand, Ledge Headwear. Online and in stores. Check it out here.

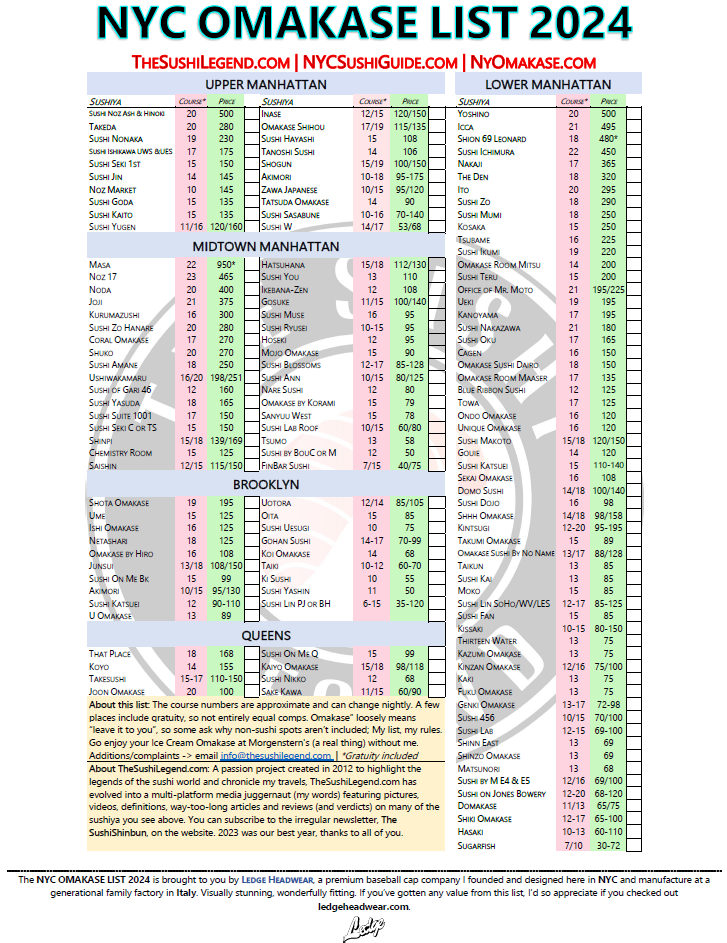

Every year I publish a list of Omakase-focused sushiya in New York

Doing 18 hours of manual labour changes a person. You notice patterns, some real, others straight from the movie The Number 23 (94% sure I’m the only one who saw this). Like, for instance, a significant number of sushiya that sounds and look the same.

_________ Omakase.

Omakase By ________.

Sushi by ______.

I can’t keep up.

I have a term for these paint-by-numbers sushiya.

Chalkboard Omakase.

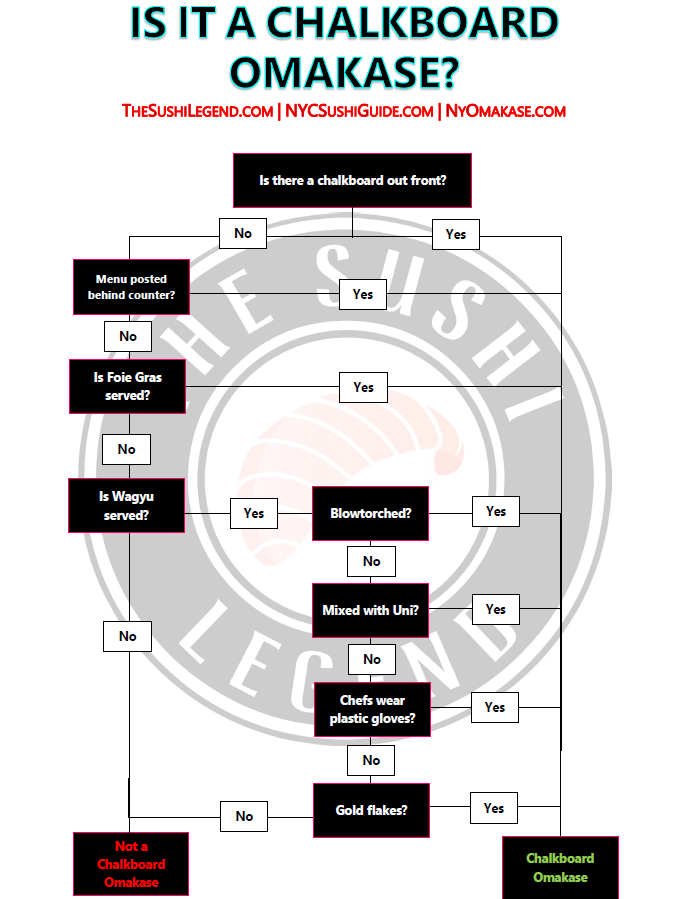

The chalkboard has the price, it sometimes has the menu. Most of it all, it rarely changes.

Inside, there’s often a few hallmarks. The blowtorch makes an appearance once (or five times). It’s sometimes paired with Wagyu Beef, that bastion of Japanese cuisine that has no place anywhere near sushi.

Side note: these sushiya don’t just advertise normal Wagyu. It’s always A5 Wagyu, the highest possible grade. To say I’m skeptical that every wagyu I’m served is the best would be an understatement.

And it’s not just the blowtorch. There’s gold flakes. Caviar. Shit, even Foie Gras. How hard is it to taste the rice when there’s 3 inches of goose liver on top? Answer: very hard.

How do you know for sure if you’re at a Chalkboard Omakase? After all, you can’t just reach me at all hours. I’m not Batman.

Fear not, I came up with a handy flowchart.

You might be asking why it matters. Fair question. |

Nothing bothers me more than businesses that appeal to the lowest common denominator.

And this is that. It’s easy to toss a bunch of fatty stuff in together, mix it up, and away you go. But that’s not what sushi is. Sushi is about the understated balance between vinegared rice and a topping. Most of all, it’s about the dance between simplicity and complexity.

Yes, the nigiri below looks simple. But years of training have gone into making that shari and preparing that Kohada; it’s why you don’t see it on many sushiya menus, and it’s why so many sushi rookies are so shocked how challenging sushi is to master.

So when the blowtorch starts coming out, or you dump uni, wagyu and toro together, those aren’t just cheat codes; they’re sending sushi in this country backwards to the time of Dawson’s Creek. This require no expertise. I can go to my local Japanese market today, pick that stuff up, mix it together, and have it taste pretty close. It also completely misses the point of Omakase. At its core, Omakase is about trusting the chef to serve what they have on hand that day. It’s not a set menu like we’ve become familiar with stateside. There’s a different word for that: Okimari. So now the sushi scene in New York is massive, but little variety. It essentially boils down to this. ▪ There’s the four hundo club (omakase-focused sushiya over/around $400). 10% And most people can fairly only afford the third group, so you’re left with a whole generation that thinks salmon with tomatoes is great sushi rather than what it actually is: breakfast. I hate Los Angeles with a fiery passion, but sushiya there embrace the more traditional spirit. For instance, at Sushi Park, that abomination of celebrity and paparazzi culture, their Omakase just continues until you tell them to stop. No chalkboard, no set menu. Yes, it’s not good, but that’s not the point. |