Note: this interview originally appeared in my regular newsletter. You can sign up for it here.

Legends, I have great news.

The incomparable Pete Wells, the restaurant critic from the New York Times and one of the most influential figures in food writing (my words, not his) kindly agreed to answer a few questions on the rise of Sushi’s popularity.

I hope I don’t lose my Cynic’s Association of North America card for this, but the man is a food writing savant and I’m extremely but pleasantly surprised he lowered himself from the penthouse to the boiler room to have a discussion with me.

It’s been an insane decade

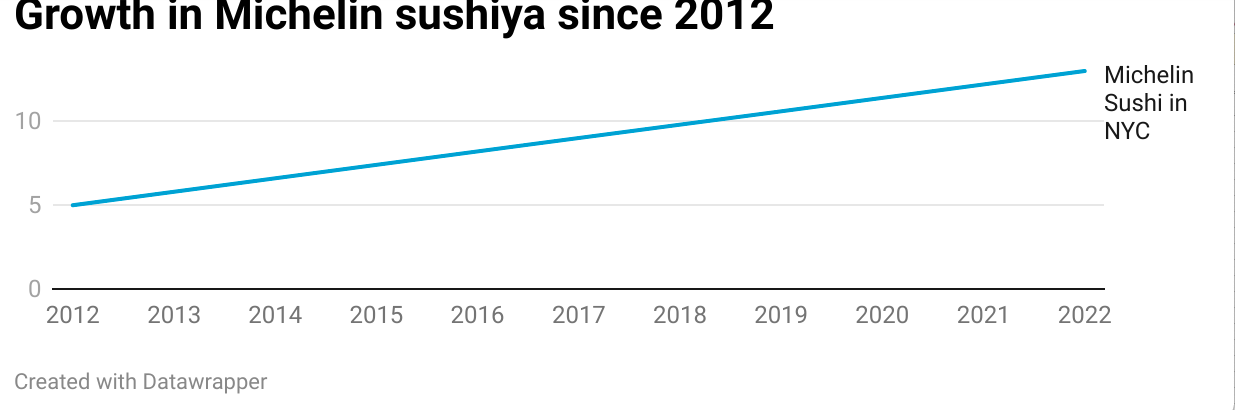

I mention it all the time, but it’s truly nuts where the New York City sushi scene is in 2023. Here’s the data:

| ▪ | 250+ sushiya (likely closer to 500) |

| ▪ | 120+ are Omakase focused |

| ▪ | 60 of those 120 are $100+ |

| ▪ | 13 Sushiya have Michelin stars |

But it wasn’t always this way. It’s easy to forget how different things were 11 years ago. To make it easier – I put together a handy table (using Michelin stars since I couldn’t find any other data point from 2012).

Yes, restaurants opening isn’t exactly a phenomenon, but let’s just agree that everything has changed in the past decade.

Let’s talk about 2012

If you trace the growth back as I did using a multiple regression model (just take my word for it), I think you can pinpoint the shift in 2012.

What happened in 2012? Three key things:

| 1. | April 2012: Instagram debuts on Android. 50 million new users join instantly. |

| 2. | July 2012/August 2012: Jiro Dreams of Sushi releases on Netflix |

| 3. | September 2012: Pete Wells give Ichimura at Brushstroke 3 stars in the New York Times. |

My original draft had a fourth thing: that I moved to New York City from Toronto in October 2012.

But my wife aka editor removed it because I’m – in her words – a “narcissistic troll”.

Well then.

The impact of the 2012 review

It’s easy to forget now, but sushi was an afterthought in the stratusphere of fine dining back in 2012. Anecdotaly, there was a broader perception that primarily non-cooked food required less skill and cost.

Of course, this ignored the fact that rice is cooked, sushi takes decades of skill and focus to master, and there’s much more to the cuisine than a California Roll.

So when Pete gave Ichimura three stars in the New York Times, that was a big deal. It signaled that great Sushi does belong in the conversation with the Per Ses and Le Bernardins of the world.

For many people who subscribe to The Sushi Legend, that probably was not news. But for the people that sit on their couch reading the New York Times every morning? It was.

Eater covered the review. So did Mediate, the Times of India and a little known blog called ‘The Sushi Legend’ that published its first ever review 2 months later.

I asked Pete that – as he looks back 11 years later – what his perspective is on that review and the impact it had on sushi in New York:

[Pete’s comments are included verbatim in italics]

Pete:

I truly don’t know what its impact was but I can tell you what I was trying to do. At the time it seemed to me that a lot of New Yorkers who were pretty sophisticated about other kinds of restaurants didn’t know how to talk about sushi-yas. You always heard the same cliches—“so fresh it jumps off the plate” or something like that. And you heard people say that sushi chefs didn’t do any “real” cooking—the idea was that they just bought the fish and served it. After my first meal at Ichimura at Brushstroke, I knew that I wanted readers to understand that there really were an array of methods and distinct preparations that the chef would then modify and adapt. So I tried to find out what Mr. Ichimura was doing that made his sushi stand out.

His publicist ended up putting me on a phone call with Mr. Ichimura and a bilingual manager at Brushstroke and I just fired all my questions at them. That was my first real education in the meaning of Edomae and the various techniques associated with it like konbujime. Then I had a separate conversation with David Bouley about aging and curing fish and the ikejime method of killing them. The review was really trying to say, Look, there is a level at which sushi making becomes just as nuanced, technique-driven and personal as any other style of cuisine.

Me again: For what it’s worth, I still hear “so fresh it jumps off the plate”. Most ingredients require time to develop flavor and – in many cases – time and methods like Kobujime (as Pete noted) only enhance the flavor.

How things have changed

Re-reading Pete’s review, one particular passage stood out:

I ate with a guest in an empty sushi bar in TriBeCa. During the two hours we sat there, no customers arrived to claim the six other counter seats or the four chairs at a nearby table.

I mentioned to Pete how hard is to imagine any sushiya of repute being even close to empty in 2023, and asked how he thinks sushi in New York has changed in the past 11 years, for better or worse?

Pete:

Well, it’s changed for the better in terms of what’s out there. When chefs like Kunihide Nakajima, Tadashi Yoshida and Shion Uino are choosing to work here—not just send apprentices but actually set up their own shops—you know you’ve got a sushi scene that for the first time is clearly more interesting than Los Angeles’s, and L.A. had a big head start. And I think that’s partly a reflection of the audience, which is just a lot more appreciative of top-level sushi. And they’ll pay for it, which points toward a change for the worse: Keeping up with the sushi scene has become really outrageously expensive. As I imagine you have noticed!

Yes, my bank account is begging for mercy. Ps: I promise I didn’t ask Pete to indirectly mention that the NYC sushi scene outstrips LA’s.

Recent liberties with the spirit of Omakase

One obvious change has been the number of NYC sushiya that offer/specialize in an Omakase. Approximately 50% of these sushiya price their Omakase under $100, move quickly and keep their menu set. In some cases, they even chisel the menu in wood behind the counter.

To some, that type of set menu contradicts the spirit of Omakase – to leave it to the chef/itamae based on what is in season that day.

To others, they’re a gateway into this world and a lesson in sushi customs/etiquette for people that otherwise wouldn’t experience it.

I asked Pete his thoughts:

I don’t like to see people cheated, but as long as everybody’s honest about what they’re selling, I can’t see a problem with cheap, short omakase menus. The truth is that even in the most expensive sushi-yas, everybody’s eating the same menu. Chefs generally aren’t struck by some wild inspiration halfway through dinner. The 6pm seating and the 9pm seating tend to be served the same fish in the same order. So why is that a problem at the less expensive sushi-yas?

He’s right, of course, and interestingly, the whims of a chef is an area that Los Angeles might be further ahead than New York.

A massive thanks to Pete Wells

I’m always fascinated when people revisit their own content with the perspective of time and wisdom of hindsight. Pete’s commentary 11 years later was illuminating for that reason (plus many others).

What makes Pete so unique as a writer is how descriptive he is for food without sounding pretentious. 99% of us default to empty phrases like “so delicious” or “like butter” or “would commit war crimes for it” (okay maybe just me), but not Pete. The next step is to go to a sushiya together – we both like to stay incognito, so it’s a match made in heaven.

Thanks, Pete.